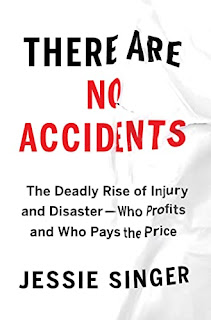

from There Are No Accidents: The Deadly Rise of Injury and Disaster―Who Profits and Who Pays the Price by Jessie Singer:

The chief consequence of blame is the prevention of prevention. In finding fault with a person, the case of any give accident appears closed.

Studies show that this simple act—finding someone to blame—makes people less likely to see systemic problems or seek systemic changes. One prompted subjects with news stories about a wide variety of accidents: financial mistakes, plane crashes, industrial disasters. When the story blamed human error, the reader was more intent on punishment and less likely to question the built environment or seek investigation of organizations behind the accident. No matter the accident, blame took the place of prevention.

You can find a prime example of this in your bicycle helmet: a basic, low-cost shock absorber. Upon contact with a hard surface, the helmet absorbs some of the impact, reducing the risk of a concussion. When the helmet is absent, blame steps in.

Helmets help, to a point. If you are cycling on a rural road, hit a pothole, and fly off your bicycle, a helmet would act as a significant injury preventer, cushioning the impact. But if you are cycling on an urban road and a 4,000-pound car or a 13,000-pound truck runs you over, you and your helmet would be crushed.

Despite these fact, in the aftermath of a bicycle accident, the helmet-wearing or helmetless status of the person on the bicycle is almost always mentioned; it appears regularly in news coverage and accident reports. When a drunk driver killed Eric, the New York Times pointed out that he was not wearing a helmet. He was also struck head-on by a 2000 BMW 528i, weighing 3,495 pounds and traveling around 60 miles per hour. Mentioning whether or not Eric wore a helmet is akin to blaming an egg for cracking against a pan.

No comments:

Post a Comment