from The Beauty of Living: e. e. cummings in the Great War by J. Alison Rosenblitt:

Also on the board of the Monthly was John Dos Passos, the future novelist, later famous for his U.S.A. trilogy. Dos (as they called him) was to become one of Cummings’s most intimate and trusted friends: the kind of friend who could always cheer him up and the kind of friend of such long standing that he could sign notes to Cummings in late life, “me.” The older Dos was friendly, genial, bighearted, and happily married with somewhat rambunctious children. Even when Cummings was middle-aged, curmudgeonly, and grumpy at being forced to receive unwanted guests, he had to admit, however grudgingly, that seeing Dos did him good.

Dos was of Portuguese descent (from the island of Madeira) along his father’s father’s line, and he stood out from the mostly Anglo-Saxon Protestant world of Harvard. His face was intellectual, with dark hair, dark eyebrows, and dark eyes under circular, wire-rimmed spectacles. His features presented a jumbled geometry. His eyebrows each descried a perfect parabola, the eyes exactly double-pointed ovals beneath the circular glasses, the philtrum under his nose a deep, ridged triangle, and the lines of his cheeks so pronounced that they drew a line exactly continuing the slope of the side of his nose down to the corners of his mouth. The complete effect would have been that of an early twentieth-century nerd, were the eyes not so mild and sensitive.

Thursday, November 30, 2023

Wednesday, November 29, 2023

the last book I ever read (The Beauty of Living: e. e. cummings in the Great War, excerpt three)

from The Beauty of Living: e. e. cummings in the Great War by J. Alison Rosenblitt:

As Cummings grew up, he perceived before he rebelled. While the marriage between the Reverend and Rebecca appears to have been, for the most part, a happy one, Cummings glimpsed a cruel side to it as well. He heard his father criticize Rebecca’s management of the household expenses as a waste of his “hard earned money,” while he rubbed it in her face that she had been penniless at the time of her marriage. Rebecca was thirty-two when they married; Cummings was born six years later, and by the time she gave birth to Elizabeth, she was in her mid-forties. She came into herself with motherhood, growing in confidence as a mother and as a person. In youth, there was an open freshness in her face. She had dark, well-defined eyebrows over bright, slightly merry eyes, and an equivocal but amused smile. She was only five foot four, and after bearing children, she took on a certain stolidity. The youthful brightness in her eyes settled into a heavier face and a large personage, which exuded love and a quality of sturdily downward anchoring. The Reverend told her that she was fat; he nettled her with sarcasm about her “swan-like neck.” Cummings saw tears in her eyes, and hated his father for it.

As Cummings grew up, he perceived before he rebelled. While the marriage between the Reverend and Rebecca appears to have been, for the most part, a happy one, Cummings glimpsed a cruel side to it as well. He heard his father criticize Rebecca’s management of the household expenses as a waste of his “hard earned money,” while he rubbed it in her face that she had been penniless at the time of her marriage. Rebecca was thirty-two when they married; Cummings was born six years later, and by the time she gave birth to Elizabeth, she was in her mid-forties. She came into herself with motherhood, growing in confidence as a mother and as a person. In youth, there was an open freshness in her face. She had dark, well-defined eyebrows over bright, slightly merry eyes, and an equivocal but amused smile. She was only five foot four, and after bearing children, she took on a certain stolidity. The youthful brightness in her eyes settled into a heavier face and a large personage, which exuded love and a quality of sturdily downward anchoring. The Reverend told her that she was fat; he nettled her with sarcasm about her “swan-like neck.” Cummings saw tears in her eyes, and hated his father for it.

Tuesday, November 28, 2023

the last book I ever read (The Beauty of Living: e. e. cummings in the Great War, excerpt two)

from The Beauty of Living: e. e. cummings in the Great War by J. Alison Rosenblitt:

Cummings’s mother adored him.

We have, thanks to her, every physical scrap of his childhood enshrined in the Harvard Library archives. She adored him to the point of absurdity; she saved every piece of paper he touched. There is page after page of baby’s first scribbles. Any mother might save her child’s first effort at pencil to paper, but Rebecca Cummings saved dozens and dozens: sheets with no more than a pencil scratch across the page, or a gashed zigzag. Some have got as far as a wobbly sort of spiral. There is something endearing but faintly ridiculous in the preservation of these aged and fragile sheets in Harvard’s plush archival space, for the benefit of the researcher, who turns them ever so carefully, fingertips on the corners of the page.

Cummings’s mother adored him.

We have, thanks to her, every physical scrap of his childhood enshrined in the Harvard Library archives. She adored him to the point of absurdity; she saved every piece of paper he touched. There is page after page of baby’s first scribbles. Any mother might save her child’s first effort at pencil to paper, but Rebecca Cummings saved dozens and dozens: sheets with no more than a pencil scratch across the page, or a gashed zigzag. Some have got as far as a wobbly sort of spiral. There is something endearing but faintly ridiculous in the preservation of these aged and fragile sheets in Harvard’s plush archival space, for the benefit of the researcher, who turns them ever so carefully, fingertips on the corners of the page.

Monday, November 27, 2023

the last book I ever read (The Beauty of Living: e. e. cummings in the Great War, excerpt one)

from The Beauty of Living: e. e. cummings in the Great War by J. Alison Rosenblitt:

E. E. Cummings grew up in Cambridge, Massachusetts, in a house about eight minutes’ walk from Harvard Yard. His neighbors were Harvard professors and his childhood was spent in the shadow of the university. His high school, the Cambridge Latin School, sat at the end of his road, and the tops of the grand Harvard buildings are visible from its grounds. Cummings’s childhood home still stands today at 104 Irving Street. It is the only house in the area with an 8-foot-high picket fence and a tight, unfriendly ring of evergreen trees, suggesting that its present owners have endured their fill of curious tourists.

E. E. Cummings grew up in Cambridge, Massachusetts, in a house about eight minutes’ walk from Harvard Yard. His neighbors were Harvard professors and his childhood was spent in the shadow of the university. His high school, the Cambridge Latin School, sat at the end of his road, and the tops of the grand Harvard buildings are visible from its grounds. Cummings’s childhood home still stands today at 104 Irving Street. It is the only house in the area with an 8-foot-high picket fence and a tight, unfriendly ring of evergreen trees, suggesting that its present owners have endured their fill of curious tourists.

Sunday, November 19, 2023

the last book I ever read (The Netanyahus: An Account of a Minor and Ultimately Even Negligible Episode in the History of a Very Famous Family, excerpt seven)

from The Netanyahus: An Account of a Minor and Ultimately Even Negligible Episode in the History of a Very Famous Family by Joshua Cohen, the 2022 Pulitzer Prize winner for Fiction:

He’d stopped again, outside the hammering and screwing elves in the window of Maclee’s Hardware. “I’d only ask one favor.”

He’d stopped again, outside the hammering and screwing elves in the window of Maclee’s Hardware. “I’d only ask one favor.”

Saturday, November 18, 2023

the last book I ever read (The Netanyahus: An Account of a Minor and Ultimately Even Negligible Episode in the History of a Very Famous Family, excerpt six)

from The Netanyahus: An Account of a Minor and Ultimately Even Negligible Episode in the History of a Very Famous Family by Joshua Cohen, the 2022 Pulitzer Prize winner for Fiction:

Edith said, “The Susquehanna.”

“That’s what I said,” and who knew—maybe Tzila was correct? Perhaps she knew the native pronunciation? After all, as she’d later tell Edith, her parents had moved from Lithuanian Poland to pre-State Israel via Minnesota. In about a decade, I’d hear the same English again in speeches by Golda Meir, who’d grown up the daughter of immigrant parents in Wisconsin. That odd mixture of Israel and the Northwest Territories.

Edith said, “The Susquehanna.”

“That’s what I said,” and who knew—maybe Tzila was correct? Perhaps she knew the native pronunciation? After all, as she’d later tell Edith, her parents had moved from Lithuanian Poland to pre-State Israel via Minnesota. In about a decade, I’d hear the same English again in speeches by Golda Meir, who’d grown up the daughter of immigrant parents in Wisconsin. That odd mixture of Israel and the Northwest Territories.

Friday, November 17, 2023

the last book I ever read (The Netanyahus: An Account of a Minor and Ultimately Even Negligible Episode in the History of a Very Famous Family, excerpt five)

from The Netanyahus: An Account of a Minor and Ultimately Even Negligible Episode in the History of a Very Famous Family by Joshua Cohen, the 2022 Pulitzer Prize winner for Fiction:

“Disgusting, Alter,” my mother said and Edith, one-handing a tilting stack of dessert plates, tried to take my father’s, but he held onto it.

“It’s empty,” Edith said, “You’re finished.”

“I’m not,” my father said and slapped his spoon onto the plate like striking a gong and, when nothing shattered, let it go. “In America,” he returned to Judy, “they tell you to mix with non-Jews, marry non-Jews, run away from your tradition, get a new name, get a new nose, change who you are, eat a turkey like an Indian, and in return you get fairness. That’s the deal. And so you change it all and then go to collect this fairness you were promised but all the offices where you make your claim are closed, because this country never holds up its half of the bargain. And even if it does, even if it treats you fair by accident maybe, or maybe only by treating someone else next to you more unfair and you feel better when you compare yourself, there will still always come some problem that fairness can’t solve, and the moment it does, everyone jumps overboard from the sinking ship and rushes back to the people they came from.”

“Disgusting, Alter,” my mother said and Edith, one-handing a tilting stack of dessert plates, tried to take my father’s, but he held onto it.

“It’s empty,” Edith said, “You’re finished.”

“I’m not,” my father said and slapped his spoon onto the plate like striking a gong and, when nothing shattered, let it go. “In America,” he returned to Judy, “they tell you to mix with non-Jews, marry non-Jews, run away from your tradition, get a new name, get a new nose, change who you are, eat a turkey like an Indian, and in return you get fairness. That’s the deal. And so you change it all and then go to collect this fairness you were promised but all the offices where you make your claim are closed, because this country never holds up its half of the bargain. And even if it does, even if it treats you fair by accident maybe, or maybe only by treating someone else next to you more unfair and you feel better when you compare yourself, there will still always come some problem that fairness can’t solve, and the moment it does, everyone jumps overboard from the sinking ship and rushes back to the people they came from.”

Thursday, November 16, 2023

the last book I ever read (The Netanyahus: An Account of a Minor and Ultimately Even Negligible Episode in the History of a Very Famous Family, excerpt four)

from The Netanyahus: An Account of a Minor and Ultimately Even Negligible Episode in the History of a Very Famous Family by Joshua Cohen, the 2022 Pulitzer Prize winner for Fiction:

Netanyahu is just such a man, afflicted with the hubris of the wounded intelligentsia. His temperament, which might have qualified him for history, disqualifies him from teaching it. Unfortunately, I know of no position in the history field without its share of teaching and bureaucratic duties, both of which Netanyahu feels are trivial and beneath him.

Instead, what his mind and mood are best-suited to is individual scholarship, research without the burden of advisorships and paperwork, without even the burden of publication. Regrettably, that is not the sort of sinecure that academia often provides, except to the engineers and physicists who develop weapons. And it is surely something that should not be expected by an obscure quarrelsome foreigner in the humanities.

Netanyahu is just such a man, afflicted with the hubris of the wounded intelligentsia. His temperament, which might have qualified him for history, disqualifies him from teaching it. Unfortunately, I know of no position in the history field without its share of teaching and bureaucratic duties, both of which Netanyahu feels are trivial and beneath him.

Instead, what his mind and mood are best-suited to is individual scholarship, research without the burden of advisorships and paperwork, without even the burden of publication. Regrettably, that is not the sort of sinecure that academia often provides, except to the engineers and physicists who develop weapons. And it is surely something that should not be expected by an obscure quarrelsome foreigner in the humanities.

Wednesday, November 15, 2023

the last book I ever read (The Netanyahus: An Account of a Minor and Ultimately Even Negligible Episode in the History of a Very Famous Family, excerpt three)

from The Netanyahus: An Account of a Minor and Ultimately Even Negligible Episode in the History of a Very Famous Family by Joshua Cohen, the 2022 Pulitzer Prize winner for Fiction:

Judy . . . maybe the one commonality that both Edith’s parents and mine would acknowledge was their love for her, which they expressed through the same question incessantly asked: who loves you more . . . Oma and Opa? Bubbe and Zeyde?

It was because of this competition that our holidays were vexed. Not spiritually, but logistically. We had to split our time, the tradition being to spend each night of a holiday with a different set of parents and alternating the order year to year: one year first-night supper at mine, second night at Edith’s; the next year first-night supper at Edith’s, second night at mine. I’m convinced this is the reason why the rabbis made all the major Jewish holidays last not for one night but two, at least in the Diaspora—to ensure that the Steinmetzes and the Blums wouldn’t have to mix like spoiled meat and rotten dairy.

Judy . . . maybe the one commonality that both Edith’s parents and mine would acknowledge was their love for her, which they expressed through the same question incessantly asked: who loves you more . . . Oma and Opa? Bubbe and Zeyde?

It was because of this competition that our holidays were vexed. Not spiritually, but logistically. We had to split our time, the tradition being to spend each night of a holiday with a different set of parents and alternating the order year to year: one year first-night supper at mine, second night at Edith’s; the next year first-night supper at Edith’s, second night at mine. I’m convinced this is the reason why the rabbis made all the major Jewish holidays last not for one night but two, at least in the Diaspora—to ensure that the Steinmetzes and the Blums wouldn’t have to mix like spoiled meat and rotten dairy.

Tuesday, November 14, 2023

the last book I ever read (The Netanyahus: An Account of a Minor and Ultimately Even Negligible Episode in the History of a Very Famous Family, excerpt two)

from The Netanyahus: An Account of a Minor and Ultimately Even Negligible Episode in the History of a Very Famous Family by Joshua Cohen, the 2022 Pulitzer Prize winner for Fiction:

The truth was this: my wife was bored and my daughter was angry. We’d sit around the hearth, where sometimes there wasn’t any warmth, because I was actually terrible at making fires and sometimes I’d use up entire boxes of matches just trying to spark the tinder. In the rare instance that I’d get the logs to catch, I’d inevitably forget to open the flue and the den would be choked with smoke. The fire had the same problem as the family: a lack of oxygen. I recall sitting by the side of cold ashes and a 500-piece puzzle of a $500 bill, trying to fit some together into the collar of that great protectionist William McKinley, aware but unable to communicate my awareness that the true puzzle to work on was us. Edith wanted a proper degree and a job that had her reading books, not just cataloging them; Judy wanted to get out of the house and be free of her nose, which she thought was too long, too big, too bumpy. Our house—like so many in our neighborhood, a Dutch Colonial, or, as it should perhaps more accurately be called, a Dutch Colonial Revival, because it dated from just after the Civil War when people were feeling nostalgic—was old and drafty and crumbling. I’d initially been in love with its clapboarded and shuttered austerity, but after a year of coming and going I’d become suspicious of its double-identity. Look at a Dutch Colonial from the front, it looks like a house. Look at a Dutch Colonial from the side, it looks like a barn. This bothered me. It made me uncertain as to whether we were humans or animals. And though there was so much to do to prepare the house for the winter—because last winter had left its lessons, especially on the shingling—I tended to procrastinate and withdraw after supper to my study upstairs. My study was at the end of the hall: a cherry-lined chamber, all my books shelved in my own order, which Edith couldn’t touch. I kept the door shut, but if I stayed still, if I stilled my breathing, I could hear her getting ready for bed. A bit later, I could hear Judy getting into bed. There would be a puddle of light under the draft of the door and then, with a click, it would dry up and vanish and, for a while at least, the only indication that I wasn’t alone in the house would be a certain stress, a certain tension, in the woodgrain, and the occasional creak of Edith rolling over, Judy’s whinny-snoring. It was during those hours that I’d put aside my taxes and turn to the Jews. That’s what I’d say—I’d get up from my desk and stretch and say, “Time for the Jews,” though sometimes I wouldn’t say it, I’d just think it, and, forsaking the research curriculum I’d set myself for the term (the commodity bubbles of the plantation economy), I’d head over to my cozy leather baseball-mitt recliner in the corner, switch on the floor lamp, and bury myself in Dr. Netanyahu, his journal articles, his journal reviews, his PhD thesis on the conversos, the Marranos, the Iberian Inquisition (Spanish and Portuguese).

The truth was this: my wife was bored and my daughter was angry. We’d sit around the hearth, where sometimes there wasn’t any warmth, because I was actually terrible at making fires and sometimes I’d use up entire boxes of matches just trying to spark the tinder. In the rare instance that I’d get the logs to catch, I’d inevitably forget to open the flue and the den would be choked with smoke. The fire had the same problem as the family: a lack of oxygen. I recall sitting by the side of cold ashes and a 500-piece puzzle of a $500 bill, trying to fit some together into the collar of that great protectionist William McKinley, aware but unable to communicate my awareness that the true puzzle to work on was us. Edith wanted a proper degree and a job that had her reading books, not just cataloging them; Judy wanted to get out of the house and be free of her nose, which she thought was too long, too big, too bumpy. Our house—like so many in our neighborhood, a Dutch Colonial, or, as it should perhaps more accurately be called, a Dutch Colonial Revival, because it dated from just after the Civil War when people were feeling nostalgic—was old and drafty and crumbling. I’d initially been in love with its clapboarded and shuttered austerity, but after a year of coming and going I’d become suspicious of its double-identity. Look at a Dutch Colonial from the front, it looks like a house. Look at a Dutch Colonial from the side, it looks like a barn. This bothered me. It made me uncertain as to whether we were humans or animals. And though there was so much to do to prepare the house for the winter—because last winter had left its lessons, especially on the shingling—I tended to procrastinate and withdraw after supper to my study upstairs. My study was at the end of the hall: a cherry-lined chamber, all my books shelved in my own order, which Edith couldn’t touch. I kept the door shut, but if I stayed still, if I stilled my breathing, I could hear her getting ready for bed. A bit later, I could hear Judy getting into bed. There would be a puddle of light under the draft of the door and then, with a click, it would dry up and vanish and, for a while at least, the only indication that I wasn’t alone in the house would be a certain stress, a certain tension, in the woodgrain, and the occasional creak of Edith rolling over, Judy’s whinny-snoring. It was during those hours that I’d put aside my taxes and turn to the Jews. That’s what I’d say—I’d get up from my desk and stretch and say, “Time for the Jews,” though sometimes I wouldn’t say it, I’d just think it, and, forsaking the research curriculum I’d set myself for the term (the commodity bubbles of the plantation economy), I’d head over to my cozy leather baseball-mitt recliner in the corner, switch on the floor lamp, and bury myself in Dr. Netanyahu, his journal articles, his journal reviews, his PhD thesis on the conversos, the Marranos, the Iberian Inquisition (Spanish and Portuguese).

Monday, November 13, 2023

the last book I ever read (The Netanyahus: An Account of a Minor and Ultimately Even Negligible Episode in the History of a Very Famous Family, excerpt one)

from The Netanyahus: An Account of a Minor and Ultimately Even Negligible Episode in the History of a Very Famous Family by Joshua Cohen, the 2022 Pulitzer Prize winner for Fiction:

My name is Ruben Blum and I’m an, yes, an historian. Soon enough, though, I guess I’ll be historical. By which I mean I’ll die and become history myself, in a rare type of transformation traditionally reserved for the purer scholars. Lawyers die and don’t become the law, doctors die and don’t turn into medicine, but biology and chemistry professors pass away and decompose into biology and chemistry, they mineralize into geology, they disperse into their science, just as surely as mathematicians become statistics. The same process holds true for us historians—in my experience, we’re the only ones in the humanities for whom this holds true—the only ones who become what we study; we age, we yellow, we go wrinkled and brittle along with our materials until our lives subside into the past, to become the very substance of time. Or maybe that’s just the Jew in me talking . . . Goys believe in the Word becoming Flesh, but Jews believe in the Flesh becoming Word, a more natural, rational incarnation . . .

By way of further introduction, I will now quote a remark made to me by the who-shall-remain-nameless then-president of the American Historical Association, when I met him at a symposium back in my student days just after the Second World War: “Ah,” he said, limply pressing my hand, “Blum, did you say? A Jewish historian?”

My name is Ruben Blum and I’m an, yes, an historian. Soon enough, though, I guess I’ll be historical. By which I mean I’ll die and become history myself, in a rare type of transformation traditionally reserved for the purer scholars. Lawyers die and don’t become the law, doctors die and don’t turn into medicine, but biology and chemistry professors pass away and decompose into biology and chemistry, they mineralize into geology, they disperse into their science, just as surely as mathematicians become statistics. The same process holds true for us historians—in my experience, we’re the only ones in the humanities for whom this holds true—the only ones who become what we study; we age, we yellow, we go wrinkled and brittle along with our materials until our lives subside into the past, to become the very substance of time. Or maybe that’s just the Jew in me talking . . . Goys believe in the Word becoming Flesh, but Jews believe in the Flesh becoming Word, a more natural, rational incarnation . . .

By way of further introduction, I will now quote a remark made to me by the who-shall-remain-nameless then-president of the American Historical Association, when I met him at a symposium back in my student days just after the Second World War: “Ah,” he said, limply pressing my hand, “Blum, did you say? A Jewish historian?”

Saturday, November 11, 2023

the last book I ever read (George Orwell's 1984, excerpt ten)

from 1984 by George Orwell:

“Has it ever occurred to you,” he said, “that the whole history of English poetry has been determined by the fact that the English language lacks rhymes?”

No, that particular thought had never occurred to Winston. Nor, in the circumstances, did it strike him as very important or interesting.

“Has it ever occurred to you,” he said, “that the whole history of English poetry has been determined by the fact that the English language lacks rhymes?”

No, that particular thought had never occurred to Winston. Nor, in the circumstances, did it strike him as very important or interesting.

Friday, November 10, 2023

the last book I ever read (George Orwell's 1984, excerpt nine)

from 1984 by George Orwell:

“We are the dead,” he said.

“We are the dead,” echoed Julia dutifully.

“You are the dead,” said an iron voice behind them.

They sprang apart. Winston’s entrails seemed to have turned into ice. He could see the white all round the irises of Julia’s eyes. Her face had turned a milky yellow. The smear of rouge that was still on each cheekbone stood out sharply, almost as though unconnected with the skin beneath.

“We are the dead,” he said.

“We are the dead,” echoed Julia dutifully.

“You are the dead,” said an iron voice behind them.

They sprang apart. Winston’s entrails seemed to have turned into ice. He could see the white all round the irises of Julia’s eyes. Her face had turned a milky yellow. The smear of rouge that was still on each cheekbone stood out sharply, almost as though unconnected with the skin beneath.

Thursday, November 9, 2023

the last book I ever read (George Orwell's 1984, excerpt eight)

from 1984 by George Orwell:

None of the three superstates ever attempts any maneuvre which involves the risk of serious defeat. When any large operation is undertaken, it is usually a surprise attack against an ally. The strategy that all three powers are following, or pretend to themselves that they are following, is the same. The plan is, by a combination of fighting, bargaining, and well-timed strokes of treachery, to acquire a ring of bases completely encircling one or other of the rival states, and then to sign a pact of friendship with that rival and remain on peaceful terms for so many years as to lull suspicion to sleep. During this time rockets loaded with atomic bombs can be assembled at all the strategic spots; finally they will all be fired simultaneously, with effects so devastating as to make retaliation impossible. It will then be time to sign a pact of friendship with the remaining world power, in preparation for another attack. This scheme, it is hardly necessary to say, is a mere daydream, impossible of realization. Moreover, no fighting ever occurs except in the disputed areas round the Equator and the Pole: no invasion of enemy territory is ever undertaken. This explains the fact that in some places the frontiers between the superstates are arbitrary. Eurasia, for example, could easily conquer the British Isles, which are geographically part of Europe, or on the other hand it would be possible for Oceania to push its frontiers to the Rhine or even to the Vistula. But this would violate the principle, followed on all sides though never formulated, of cultural integrity. If Oceania were to conquer the areas that used once to be known as France and Germany, it would be necessary either to exterminate the inhabitants, a task of great physical difficulty, or to assimilate a population of about a hundred million people, who, so far as technical development goes, are roughly on the Oceanic level. The problem is the same for all three superstates. It is absolutely necessary to their structure that there should be no contact with foreigners except, to a limited extent, with war prisoners and colored slaves. Even the official ally of the moment is always regarded with the darkest suspicion. War prisoners apart, the average citizen of Oceania never sets eyes on a citizen of either Eurasia or Eastasia, and he is forbidden the knowledge of foreign languages. If he were allowed contact with foreigners he would discover that they are creatures similar to himself and that most of what he has been told about them is lies. The sealed world in which he lives would be broken, and the fear, hatred, and self-righteousness on which his morale depends might evaporate. It is therefore realized on all sides that however often Persia, or Egypt, or Java, or Ceylon may change hands, the main frontiers must never be crossed by anything except bombs.

None of the three superstates ever attempts any maneuvre which involves the risk of serious defeat. When any large operation is undertaken, it is usually a surprise attack against an ally. The strategy that all three powers are following, or pretend to themselves that they are following, is the same. The plan is, by a combination of fighting, bargaining, and well-timed strokes of treachery, to acquire a ring of bases completely encircling one or other of the rival states, and then to sign a pact of friendship with that rival and remain on peaceful terms for so many years as to lull suspicion to sleep. During this time rockets loaded with atomic bombs can be assembled at all the strategic spots; finally they will all be fired simultaneously, with effects so devastating as to make retaliation impossible. It will then be time to sign a pact of friendship with the remaining world power, in preparation for another attack. This scheme, it is hardly necessary to say, is a mere daydream, impossible of realization. Moreover, no fighting ever occurs except in the disputed areas round the Equator and the Pole: no invasion of enemy territory is ever undertaken. This explains the fact that in some places the frontiers between the superstates are arbitrary. Eurasia, for example, could easily conquer the British Isles, which are geographically part of Europe, or on the other hand it would be possible for Oceania to push its frontiers to the Rhine or even to the Vistula. But this would violate the principle, followed on all sides though never formulated, of cultural integrity. If Oceania were to conquer the areas that used once to be known as France and Germany, it would be necessary either to exterminate the inhabitants, a task of great physical difficulty, or to assimilate a population of about a hundred million people, who, so far as technical development goes, are roughly on the Oceanic level. The problem is the same for all three superstates. It is absolutely necessary to their structure that there should be no contact with foreigners except, to a limited extent, with war prisoners and colored slaves. Even the official ally of the moment is always regarded with the darkest suspicion. War prisoners apart, the average citizen of Oceania never sets eyes on a citizen of either Eurasia or Eastasia, and he is forbidden the knowledge of foreign languages. If he were allowed contact with foreigners he would discover that they are creatures similar to himself and that most of what he has been told about them is lies. The sealed world in which he lives would be broken, and the fear, hatred, and self-righteousness on which his morale depends might evaporate. It is therefore realized on all sides that however often Persia, or Egypt, or Java, or Ceylon may change hands, the main frontiers must never be crossed by anything except bombs.

Wednesday, November 8, 2023

the last book I ever read (George Orwell's 1984, excerpt seven)

from 1984 by George Orwell:

Four, five, six—seven times they met during the month of June. Winston had dropped his habit of drinking gin at all hours. He seemed to have lost the need for it. He had grown fatter, his varicose ulcer had subsided, leaving only a brown stain on the skin above his ankle, his fits of coughing in the early morning had stopped. The process of life had ceased to be intolerable, he had no longer any impulse to make faces at the telescreen or shout curses at the top of his voice. Now that they had a secure hiding place, almost a home, it did not even seem a hardship that they could only meet infrequently and for a couple of hours at a time. What mattered was that the room over the junk shop should exist. To know that it was there, inviolate, was almost the same as being in it. The room was a world, a pocket of the past where extinct animals could walk. Mr. Charrington, thought Winston, was another extinct animal. He usually stopped to talk with Mr. Charrington for a few minutes on his way upstairs. The old man seemed seldom or never to go out of doors, and on the other hand to have almost no customers. He led a ghostlike existence between the tiny, dark shop, and an even tinier back kitchen where he prepared his meals and which contained, among other things, an unbelievably ancient gramophone with an enormous horn. He seemed glad of the opportunity to talk. Wandering about among his worthless stock, with his long nose and thick spectacles and his bowed shoulders in the velvet jacket, he had always vaguely the air of being a collector rather than a tradesman. With a sort of faded enthusiasm he would finger this scrap of rubbish or that—a china bottle-stopper, the painted lid of a broken snuffbox, a pinchbeck locket containing a strand of some long-dead baby’s hair—never asking that Winston should buy it, merely that he should admire it. To talk to him was like listening to the tinkling of a worn-out musical box. He had dragged out from the corners of his memory some more fragments of forgotten rhymes. There was one about four and twenty blackbirds, and another about a cow with a crumpled horn, and another about the death of poor Cock Robin. “It just occurred to me you might be interested,” he would say with a deprecating little laugh whenever he produced a new fragment. But he could never recall more than a few lines of any one rhyme.

Four, five, six—seven times they met during the month of June. Winston had dropped his habit of drinking gin at all hours. He seemed to have lost the need for it. He had grown fatter, his varicose ulcer had subsided, leaving only a brown stain on the skin above his ankle, his fits of coughing in the early morning had stopped. The process of life had ceased to be intolerable, he had no longer any impulse to make faces at the telescreen or shout curses at the top of his voice. Now that they had a secure hiding place, almost a home, it did not even seem a hardship that they could only meet infrequently and for a couple of hours at a time. What mattered was that the room over the junk shop should exist. To know that it was there, inviolate, was almost the same as being in it. The room was a world, a pocket of the past where extinct animals could walk. Mr. Charrington, thought Winston, was another extinct animal. He usually stopped to talk with Mr. Charrington for a few minutes on his way upstairs. The old man seemed seldom or never to go out of doors, and on the other hand to have almost no customers. He led a ghostlike existence between the tiny, dark shop, and an even tinier back kitchen where he prepared his meals and which contained, among other things, an unbelievably ancient gramophone with an enormous horn. He seemed glad of the opportunity to talk. Wandering about among his worthless stock, with his long nose and thick spectacles and his bowed shoulders in the velvet jacket, he had always vaguely the air of being a collector rather than a tradesman. With a sort of faded enthusiasm he would finger this scrap of rubbish or that—a china bottle-stopper, the painted lid of a broken snuffbox, a pinchbeck locket containing a strand of some long-dead baby’s hair—never asking that Winston should buy it, merely that he should admire it. To talk to him was like listening to the tinkling of a worn-out musical box. He had dragged out from the corners of his memory some more fragments of forgotten rhymes. There was one about four and twenty blackbirds, and another about a cow with a crumpled horn, and another about the death of poor Cock Robin. “It just occurred to me you might be interested,” he would say with a deprecating little laugh whenever he produced a new fragment. But he could never recall more than a few lines of any one rhyme.

Tuesday, November 7, 2023

the last book I ever read (George Orwell's 1984, excerpt six)

from 1984 by George Orwell:

Julia was twenty-six years old. She lived in a hostel with thirty other girls (“ Always in the stink of women! How I hate women!” she said parenthetically), and she worked, as he had guessed, on the novel-writing machines in the Fiction Department. She enjoyed her work, which consisted chiefly in running and servicing a powerful but tricky electric motor. She was “not clever,” but was fond of using her hands and felt at home with machinery. She could describe the whole process of composing a novel, from the general directive issued by the Planning Committee down to the final touching-up by the Rewrite Squad. But she was not interested in the finished product. She “didn’t much care for reading,” she said. Books were just a commodity that had to be produced, like jam or bootlaces.

Julia was twenty-six years old. She lived in a hostel with thirty other girls (“ Always in the stink of women! How I hate women!” she said parenthetically), and she worked, as he had guessed, on the novel-writing machines in the Fiction Department. She enjoyed her work, which consisted chiefly in running and servicing a powerful but tricky electric motor. She was “not clever,” but was fond of using her hands and felt at home with machinery. She could describe the whole process of composing a novel, from the general directive issued by the Planning Committee down to the final touching-up by the Rewrite Squad. But she was not interested in the finished product. She “didn’t much care for reading,” she said. Books were just a commodity that had to be produced, like jam or bootlaces.

Monday, November 6, 2023

the last book I ever read (George Orwell's 1984, excerpt five)

from 1984 by George Orwell:

He walked on. The bomb had demolished a group of houses two hundred meters up the street. A black plume of smoke hung in the sky, and below it a cloud of plaster dust in which a crowd was already forming round the ruins. There was a little pile of plaster lying on the pavement ahead of him, and in the middle of it he could see a bright red streak. When he got up to it he saw that it was a human hand severed at the wrist. Apart from the bloody stump, the hand was so completely whitened as to resemble a plaster cast.

He walked on. The bomb had demolished a group of houses two hundred meters up the street. A black plume of smoke hung in the sky, and below it a cloud of plaster dust in which a crowd was already forming round the ruins. There was a little pile of plaster lying on the pavement ahead of him, and in the middle of it he could see a bright red streak. When he got up to it he saw that it was a human hand severed at the wrist. Apart from the bloody stump, the hand was so completely whitened as to resemble a plaster cast.

Sunday, November 5, 2023

the last book I ever read (George Orwell's 1984, excerpt four)

from 1984 by George Orwell:

He pressed his fingers against his eyelids again. He had written it down at last, but it made no difference. The therapy had not worked. The urge to shout filthy words at the top of his voice was as strong as ever.

He pressed his fingers against his eyelids again. He had written it down at last, but it made no difference. The therapy had not worked. The urge to shout filthy words at the top of his voice was as strong as ever.

Saturday, November 4, 2023

the last book I ever read (George Orwell's 1984, excerpt three)

from 1984 by George Orwell:

Winston had finished his bread and cheese. He turned a little sideways in his chair to drink his mug of coffee. At the table on his left the man with the strident voice was still talking remorselessly away. A young woman who was perhaps his secretary, and who was sitting with her back to Winston, was listening to him and seemed to be eagerly agreeing with everything that he said. From time to time Winston caught some such remark as “I think you’re so right, I do so agree with you,” uttered in a youthful and rather silly feminine voice. But the other voice never stopped for an instant, even when the girl was speaking. Winston knew the man by sight, though he knew no more about him than that he held some important post in the Fiction Department. He was a man of about thirty, with a muscular throat and a large, mobile mouth. His head was thrown back a little, and because of the angle at which he was sitting, his spectacles caught the light and presented to Winston two blank discs instead of eyes. What was slightly horrible, was that from the stream of sound that poured out of his mouth, it was almost impossible to distinguish a single word. Just once Winston caught a phrase—“ complete and final elimination of Goldsteinism”—jerked out very rapidly and, as it seemed, all in one piece, like a line of type cast solid. For the rest it was just a noise, a quack-quack-quacking. And yet, though you could not actually hear what the man was saying, you could not be in any doubt about its general nature. He might be denouncing Goldstein and demanding sterner measures against thought-criminals and saboteurs, he might be fulminating against the atrocities of the Eurasian army, he might be praising Big Brother or the heroes on the Malabar front—it made no difference. Whatever it was, you could be certain that every word of it was pure orthodoxy, pure Ingsoc. As he watched the eyeless face with the jaw moving rapidly up and down, Winston had a curious feeling that this was not a real human being but some kind of dummy. It was not the man’s brain that was speaking; it was his larynx. The stuff that was coming out of him consisted of words, but it was not speech in the true sense: it was a noise uttered in unconsciousness, like the quacking of a duck.

Winston had finished his bread and cheese. He turned a little sideways in his chair to drink his mug of coffee. At the table on his left the man with the strident voice was still talking remorselessly away. A young woman who was perhaps his secretary, and who was sitting with her back to Winston, was listening to him and seemed to be eagerly agreeing with everything that he said. From time to time Winston caught some such remark as “I think you’re so right, I do so agree with you,” uttered in a youthful and rather silly feminine voice. But the other voice never stopped for an instant, even when the girl was speaking. Winston knew the man by sight, though he knew no more about him than that he held some important post in the Fiction Department. He was a man of about thirty, with a muscular throat and a large, mobile mouth. His head was thrown back a little, and because of the angle at which he was sitting, his spectacles caught the light and presented to Winston two blank discs instead of eyes. What was slightly horrible, was that from the stream of sound that poured out of his mouth, it was almost impossible to distinguish a single word. Just once Winston caught a phrase—“ complete and final elimination of Goldsteinism”—jerked out very rapidly and, as it seemed, all in one piece, like a line of type cast solid. For the rest it was just a noise, a quack-quack-quacking. And yet, though you could not actually hear what the man was saying, you could not be in any doubt about its general nature. He might be denouncing Goldstein and demanding sterner measures against thought-criminals and saboteurs, he might be fulminating against the atrocities of the Eurasian army, he might be praising Big Brother or the heroes on the Malabar front—it made no difference. Whatever it was, you could be certain that every word of it was pure orthodoxy, pure Ingsoc. As he watched the eyeless face with the jaw moving rapidly up and down, Winston had a curious feeling that this was not a real human being but some kind of dummy. It was not the man’s brain that was speaking; it was his larynx. The stuff that was coming out of him consisted of words, but it was not speech in the true sense: it was a noise uttered in unconsciousness, like the quacking of a duck.

Friday, November 3, 2023

the last book I ever read (George Orwell's 1984, excerpt two)

from 1984 by George Orwell:

Winston sank his arms to his sides and slowly refilled his lungs with air. His mind slid away into the labyrinthine world of doublethink. To know and not to know, to be conscious of complete truthfulness while telling carefully constructed lies, to hold simultaneously two opinions which canceled out, knowing them to be contradictory and believing in both of them, to use logic against logic, to repudiate morality while laying claim to it, to believe that democracy was impossible and that the Party was the guardian of democracy, to forget whatever it was necessary to forget, then to draw it back into memory again at the moment when it was needed, and then promptly to forget it again, and above all, to apply the same process to the process itself—that was the ultimate subtlety: consciously to induce unconsciousness, and then, once again, to become unconscious of the act of hypnosis you had just performed. Even to understand the word “doublethink” involved the use of doublethink.

Winston sank his arms to his sides and slowly refilled his lungs with air. His mind slid away into the labyrinthine world of doublethink. To know and not to know, to be conscious of complete truthfulness while telling carefully constructed lies, to hold simultaneously two opinions which canceled out, knowing them to be contradictory and believing in both of them, to use logic against logic, to repudiate morality while laying claim to it, to believe that democracy was impossible and that the Party was the guardian of democracy, to forget whatever it was necessary to forget, then to draw it back into memory again at the moment when it was needed, and then promptly to forget it again, and above all, to apply the same process to the process itself—that was the ultimate subtlety: consciously to induce unconsciousness, and then, once again, to become unconscious of the act of hypnosis you had just performed. Even to understand the word “doublethink” involved the use of doublethink.

Thursday, November 2, 2023

the last book I ever read (George Orwell's 1984, excerpt one)

from 1984 by George Orwell:

Suddenly he was standing on short springy turf, on a summer evening when the slanting rays of the sun gilded the ground. The landscape that he was looking at recurred so often in his dreams that he was never fully certain whether or not he had seen it in the real world. In his waking thoughts he called it the Golden Country. It was an old, rabbit-bitten pasture, with a foot track wandering across it and a molehill here and there. In the ragged hedge on the opposite side of the field the boughs of the elm trees were swaying very faintly in the breeze, their leaves just stirring in dense masses like women’s hair. Somewhere near at hand, though out of sight, there was a clear, slow-moving stream where dace were swimming in the pools under the willow trees.

The girl with dark hair was coming toward him across the field. With what seemed a single movement she tore off her clothes and flung them disdainfully aside. Her body was white and smooth, but it aroused no desire in him; indeed, he barely looked at it. What overwhelmed him in that instant was admiration for the gesture with which she had thrown her clothes aside. With its grace and carelessness it seemed to annihilate a whole culture, a whole system of thought, as though Big Brother and the Party and the Thought Police could all be swept into nothingness by a single splendid movement of the arm. That too was a gesture belonging to the ancient time. Winston woke up with the word “Shakespeare” on his lips.

Suddenly he was standing on short springy turf, on a summer evening when the slanting rays of the sun gilded the ground. The landscape that he was looking at recurred so often in his dreams that he was never fully certain whether or not he had seen it in the real world. In his waking thoughts he called it the Golden Country. It was an old, rabbit-bitten pasture, with a foot track wandering across it and a molehill here and there. In the ragged hedge on the opposite side of the field the boughs of the elm trees were swaying very faintly in the breeze, their leaves just stirring in dense masses like women’s hair. Somewhere near at hand, though out of sight, there was a clear, slow-moving stream where dace were swimming in the pools under the willow trees.

The girl with dark hair was coming toward him across the field. With what seemed a single movement she tore off her clothes and flung them disdainfully aside. Her body was white and smooth, but it aroused no desire in him; indeed, he barely looked at it. What overwhelmed him in that instant was admiration for the gesture with which she had thrown her clothes aside. With its grace and carelessness it seemed to annihilate a whole culture, a whole system of thought, as though Big Brother and the Party and the Thought Police could all be swept into nothingness by a single splendid movement of the arm. That too was a gesture belonging to the ancient time. Winston woke up with the word “Shakespeare” on his lips.

Wednesday, November 1, 2023

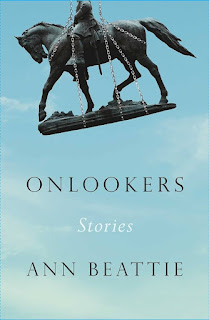

the last book I ever read (Onlookers: Stories by Ann Beattie, excerpt twelve)

from Onlookers: Stories by Ann Beattie:

“I talked to some guys who work at Lowe’s who are on call to haul Lee out of there. They’re going to bring in cranes to lift the statue part off, sort of lassoing it like a cactus. Then I guess some other company’s coming for the”—he paused—“the plink.”

She almost spoke, but didn’t. It had been a long night.

“I talked to some guys who work at Lowe’s who are on call to haul Lee out of there. They’re going to bring in cranes to lift the statue part off, sort of lassoing it like a cactus. Then I guess some other company’s coming for the”—he paused—“the plink.”

She almost spoke, but didn’t. It had been a long night.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)