from Empire of Pain: The Secret History of the Sackler Family by Patrick Radden Keefe:

Curiously, a partisan divide emerged among the state prosecutors. Red state AGs were more inclined to go along with the deal the Sacklers were proposing, whereas blue state prosecutors wanted to fight for more. Some speculated that this might be due to how dire the need for emergency funds was in the red states, or to different political cultures—Republicans more inclined to accommodate corporate interests, Democrats more given to redistributionist zeal. But another factor might have been that behind the scenes the Sacklers were actively whipping votes. The family had long understood the physics of political influence and the value of a well-connected fixer. When they needed to make the threat of felony charges go away back in 2006, they deployed the former federal prosecutor Rudy Giuliani. Now that they were facing a cohort of angry attorneys general, they put a new fixer on the payroll: a former U.S. senator from Alabama, Luther Strange, who had previously served as state AG. Until 2017, Strange had been the chairman of a national group called RAGA, or the Republican Attorneys General Association. In the past, Purdue had donated generously to this group, and to its Democratic counterpart, giving the two organizations a combined $800,000 between 2014 and 2018. Remarkably, the company continued to contribute to both groups, even after declaring bankruptcy and even as virtually every state attorney general, Democrat or Republican, was suing them. During the summer of 2019, Luther Strange took part in a RAGA meeting in West Virginia as an emissary for the Sacklers and personally lobbied the Republican AGs in attendance to support a settlement.

To further complicate matters, the plaintiffs’ lawyers, like Mike Moore, who had brought suits against Purdue on behalf of local governments and served as key allies for those trying to hold the Sacklers to account, seemed inclined to accept the settlement as well. Plaintiffs’ lawyers work on a contingency basis, taking up to a third of any final settlement in fees, which means that they sometimes have incentives of their own to seize a multibillion-dollar settlement when it is on the table, rather than take the gamble of pushing for a larger and more just result and ending up with nothing. These attorneys also regarded the Purdue case as one piece of a larger litigation puzzle, in which they were pursuing separate suits against other drugmakers, wholesalers, and pharmacies. Some of the lawyers involved in the bankruptcy suspected that Mike Moore himself might have played a hand, behind the scenes, in conceiving the deal that the Sacklers proposed in Cleveland. It would be a compromise, in which the states would get some much-needed funds to address the crisis, the Sacklers would achieve an outcome they could live with, and the plaintiffs’ lawyers would collect hundreds of millions in fees. These suspicions proved correct: Moore acknowledged, in a subsequent interview, that working with another plaintiffs’ lawyer, Drake Martin, he had “put this deal together” for Purdue.

Friday, January 27, 2023

Thursday, January 26, 2023

the last book I ever read (Empire of Pain: The Secret History of the Sackler Family, excerpt fourteen)

from Empire of Pain: The Secret History of the Sackler Family by Patrick Radden Keefe:

Nan Goldin lived. But she often felt a kind of survivor’s guilt, thinking of the friends, so many of them now gone, who stared back at her from her own photographs. Her work found new admirers. Museums ran retrospectives. Eventually, those pictures of her dead friends would hang on the walls of some of the most illustrious galleries in the world. In 2011, the Louvre opened its palatial halls to Goldin, after hours, so that she could stroll through the broad marble galleries, barefoot, and take pictures of the artworks on display, for an installation in which she juxtaposed images of paintings from the museum’s collection with photographs from her own oeuvre. The chronicler of life on the margins had become canonical.

In 2014, Goldin was in Berlin when she developed a severe case of tendinitis in her left wrist, which was causing her a great deal of pain. She went to see a doctor who wrote her a prescription for OxyContin. Goldin knew about the drug, knew its reputation for being dangerously addictive. But her own history of hard drug use, rather than making her more cautious, could sometimes mean that she was cavalier. I can handle it, she figured.

As soon as she took the pills, she could see what the fuss was about. OxyContin didn’t just ameliorate the pain in her wrist; it felt like a chemical insulation not just from pain but from anxiety and upset. The drug felt, she would say, like “a padding between you and the world.” It wasn’t long before she was taking the pills more quickly than she was supposed to. Two pills a day became four, then eight, then sixteen. To keep up with her own needs, she had to enlist other doctors and juggle multiple prescriptions. She had money; she had received a major grant to work on new material and was preparing for a show at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. But her efforts to source pills had come to feel like a full-time job. She started crushing pills and snorting them. She found an obliging dealer in New York who would ship her pills via FedEx.

Three years of her life disappeared. She was working throughout, but she was sequestered in her apartment, entirely isolated from human contact, seeing virtually no one, apart from those she needed to see to get her pills. She would spend days counting and recounting her collection of pills, making resolves and then breaking them. What kept her in this spiral was not the euphoria of the high but just the fear of withdrawal. When it hit, she could summon no words to capture the mental and physical agony. Her whole body raged with searing, incandescent pain. It felt as if the skin had been peeled right off her. She did a painting during this period of a miserable-looking young man in a green tank top, his arms festering with boils and wounds. She titled it Withdrawal/ Quicksand. At a certain point, her doctors caught on to her and she was struggling to access enough black-market OxyContin, so she lapsed back into using heroin. One night, she bought a batch that, unbeknownst to her, was actually fentanyl, and she overdosed.

Nan Goldin lived. But she often felt a kind of survivor’s guilt, thinking of the friends, so many of them now gone, who stared back at her from her own photographs. Her work found new admirers. Museums ran retrospectives. Eventually, those pictures of her dead friends would hang on the walls of some of the most illustrious galleries in the world. In 2011, the Louvre opened its palatial halls to Goldin, after hours, so that she could stroll through the broad marble galleries, barefoot, and take pictures of the artworks on display, for an installation in which she juxtaposed images of paintings from the museum’s collection with photographs from her own oeuvre. The chronicler of life on the margins had become canonical.

In 2014, Goldin was in Berlin when she developed a severe case of tendinitis in her left wrist, which was causing her a great deal of pain. She went to see a doctor who wrote her a prescription for OxyContin. Goldin knew about the drug, knew its reputation for being dangerously addictive. But her own history of hard drug use, rather than making her more cautious, could sometimes mean that she was cavalier. I can handle it, she figured.

As soon as she took the pills, she could see what the fuss was about. OxyContin didn’t just ameliorate the pain in her wrist; it felt like a chemical insulation not just from pain but from anxiety and upset. The drug felt, she would say, like “a padding between you and the world.” It wasn’t long before she was taking the pills more quickly than she was supposed to. Two pills a day became four, then eight, then sixteen. To keep up with her own needs, she had to enlist other doctors and juggle multiple prescriptions. She had money; she had received a major grant to work on new material and was preparing for a show at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. But her efforts to source pills had come to feel like a full-time job. She started crushing pills and snorting them. She found an obliging dealer in New York who would ship her pills via FedEx.

Three years of her life disappeared. She was working throughout, but she was sequestered in her apartment, entirely isolated from human contact, seeing virtually no one, apart from those she needed to see to get her pills. She would spend days counting and recounting her collection of pills, making resolves and then breaking them. What kept her in this spiral was not the euphoria of the high but just the fear of withdrawal. When it hit, she could summon no words to capture the mental and physical agony. Her whole body raged with searing, incandescent pain. It felt as if the skin had been peeled right off her. She did a painting during this period of a miserable-looking young man in a green tank top, his arms festering with boils and wounds. She titled it Withdrawal/ Quicksand. At a certain point, her doctors caught on to her and she was struggling to access enough black-market OxyContin, so she lapsed back into using heroin. One night, she bought a batch that, unbeknownst to her, was actually fentanyl, and she overdosed.

Wednesday, January 25, 2023

the last book I ever read (Empire of Pain: The Secret History of the Sackler Family, excerpt thirteen)

from Empire of Pain: The Secret History of the Sackler Family by Patrick Radden Keefe:

Given China’s fraught history with opioids—the country fought the Opium Wars in the nineteenth century to stop Britain from dumping the drug there, which had given rise to a scourge of addiction—one might assume that there would be formidable barriers to entry when it came to an effort by Mundipharma to change the culture of prescribing. But the company was ravenous for new customers and prepared to engage in marketing tactics that were extreme even by the standards of Purdue. Mundipharma China had been established back in 1993, the same year that the Arthur M. Sackler Museum of Art and Archaeology opened in Beijing. The China Medical Tribune, which Arthur had founded, now boasted a readership of more than a million Chinese doctors. In seeking to convince physicians and patients in China that opioids were not, in fact, dangerously addictive, Mundipharma assembled a huge sales force. They were under a great deal of pressure from the company to perform, and they were encouraged with the type of aggressive incentive structure that the Sacklers had always favored. Come in over the company’s quarterly sales targets and you could double your salary. Come in under and you could lose your job. Mundipharma supplied the reps with marketing materials that included assertions about the safety and effectiveness of OxyContin that had long since been debunked. The company claimed that OxyContin was the World Health Organization’s preferred treatment for cancer pain (it isn’t). According to an investigation by the Associated Press, Mundipharma reps in hospitals actually donned white coats and pretended to be doctors themselves. They consulted directly with patients about their health concerns and made copies of people’s confidential medical records.

Mundipharma released a series of flashy promotional videos about its products and its global ambitions, featuring images of smiling patients from a range of different ethnicities. “We’re only just getting started,” one of the videos said.

Given China’s fraught history with opioids—the country fought the Opium Wars in the nineteenth century to stop Britain from dumping the drug there, which had given rise to a scourge of addiction—one might assume that there would be formidable barriers to entry when it came to an effort by Mundipharma to change the culture of prescribing. But the company was ravenous for new customers and prepared to engage in marketing tactics that were extreme even by the standards of Purdue. Mundipharma China had been established back in 1993, the same year that the Arthur M. Sackler Museum of Art and Archaeology opened in Beijing. The China Medical Tribune, which Arthur had founded, now boasted a readership of more than a million Chinese doctors. In seeking to convince physicians and patients in China that opioids were not, in fact, dangerously addictive, Mundipharma assembled a huge sales force. They were under a great deal of pressure from the company to perform, and they were encouraged with the type of aggressive incentive structure that the Sacklers had always favored. Come in over the company’s quarterly sales targets and you could double your salary. Come in under and you could lose your job. Mundipharma supplied the reps with marketing materials that included assertions about the safety and effectiveness of OxyContin that had long since been debunked. The company claimed that OxyContin was the World Health Organization’s preferred treatment for cancer pain (it isn’t). According to an investigation by the Associated Press, Mundipharma reps in hospitals actually donned white coats and pretended to be doctors themselves. They consulted directly with patients about their health concerns and made copies of people’s confidential medical records.

Mundipharma released a series of flashy promotional videos about its products and its global ambitions, featuring images of smiling patients from a range of different ethnicities. “We’re only just getting started,” one of the videos said.

Tuesday, January 24, 2023

the last book I ever read (Empire of Pain: The Secret History of the Sackler Family, excerpt twelve)

from Empire of Pain: The Secret History of the Sackler Family by Patrick Radden Keefe:

African Americans had been spared the full brunt of the opioid epidemic: doctors were less likely to prescribe opioid painkillers to Black patients, either because they did not trust them to take the drugs responsibly or because they were less likely to feel empathy for these patients and want to treat their pain aggressively. As a result, levels of addiction and death were statistically low among African Americans. It appeared to be a rare instance in which systemic racism could be said to have protected the community. But people of color were disproportionately affected by the war on drugs. Purdue executives might have evaded jail time for their role in a scheme that generated billions of dollars for Madeleine’s family, but in 2016, Indiana’s governor, Mike Pence, signed a law reinstating a mandatory minimum sentence for any street-level dealer who was caught selling heroin and had a prior conviction: ten years. Nationwide, 82 percent of those charged with heroin trafficking were Black or Latino.

African Americans had been spared the full brunt of the opioid epidemic: doctors were less likely to prescribe opioid painkillers to Black patients, either because they did not trust them to take the drugs responsibly or because they were less likely to feel empathy for these patients and want to treat their pain aggressively. As a result, levels of addiction and death were statistically low among African Americans. It appeared to be a rare instance in which systemic racism could be said to have protected the community. But people of color were disproportionately affected by the war on drugs. Purdue executives might have evaded jail time for their role in a scheme that generated billions of dollars for Madeleine’s family, but in 2016, Indiana’s governor, Mike Pence, signed a law reinstating a mandatory minimum sentence for any street-level dealer who was caught selling heroin and had a prior conviction: ten years. Nationwide, 82 percent of those charged with heroin trafficking were Black or Latino.

Monday, January 23, 2023

the last book I ever read (Empire of Pain: The Secret History of the Sackler Family, excerpt eleven)

from Empire of Pain: The Secret History of the Sackler Family by Patrick Radden Keefe:

“Our first month of work for Purdue was quite busy,” Dezenhall wrote to Howard Udell in late 2001. He was particularly proud of an opinion column he had managed to arrange in the New York Post that blamed “rural-area drug abusers” and “the liberals” for cooking up a fake controversy over OxyContin. When the article ran, Dezenhall sent it to Udell, Hogen, and Friedman with a promise that he could turn around the negative narrative. “The anti-story begins,” he wrote.

Dezenhall worked closely with a psychiatrist named Sally Satel who was a fellow at a conservative think tank, the American Enterprise Institute. Satel published an essay in the Health section of The New York Times in which she argued that hysteria over opioids had made American physicians fearful of prescribing much-needed pain medication. “When you scratch the surface of someone who is addicted to painkillers,” Satel wrote, “you usually find a seasoned drug abuser with a previous habit involving pills, alcohol, heroin or cocaine.” In the article, she cited an unnamed colleague, and a study in the Journal of Analytical Toxicology, but did not mention that the colleague actually worked for Purdue. Or that the study had been funded by Purdue and written by Purdue employees. Or that she had shown a copy of her essay, in advance, to a Purdue official (he liked it). Or that Purdue was donating $50,000 a year to her institute at AEI.

“Our first month of work for Purdue was quite busy,” Dezenhall wrote to Howard Udell in late 2001. He was particularly proud of an opinion column he had managed to arrange in the New York Post that blamed “rural-area drug abusers” and “the liberals” for cooking up a fake controversy over OxyContin. When the article ran, Dezenhall sent it to Udell, Hogen, and Friedman with a promise that he could turn around the negative narrative. “The anti-story begins,” he wrote.

Dezenhall worked closely with a psychiatrist named Sally Satel who was a fellow at a conservative think tank, the American Enterprise Institute. Satel published an essay in the Health section of The New York Times in which she argued that hysteria over opioids had made American physicians fearful of prescribing much-needed pain medication. “When you scratch the surface of someone who is addicted to painkillers,” Satel wrote, “you usually find a seasoned drug abuser with a previous habit involving pills, alcohol, heroin or cocaine.” In the article, she cited an unnamed colleague, and a study in the Journal of Analytical Toxicology, but did not mention that the colleague actually worked for Purdue. Or that the study had been funded by Purdue and written by Purdue employees. Or that she had shown a copy of her essay, in advance, to a Purdue official (he liked it). Or that Purdue was donating $50,000 a year to her institute at AEI.

Sunday, January 22, 2023

the last book I ever read (Empire of Pain: The Secret History of the Sackler Family, excerpt ten)

from Empire of Pain: The Secret History of the Sackler Family by Patrick Radden Keefe:

Shortly after Rudolph Giuliani stepped down from his position as mayor of New York City, he went into business as a consultant, and one of his first clients was Purdue. When he entered the private sector, Giuliani was looking to make a lot of money quickly. In 2001, he had a net worth of $1 million; five years later, he would report $17 million in income and some $50 million in assets. For Purdue, which was working hard to frame OxyContin abuse as a law enforcement problem, rather than an issue that might implicate the drug itself or the way it was marketed, the former prosecutor who had led New York City after the 9/ 11 attacks would make an ideal fixer. In Michael Friedman’s view, Giuliani was “uniquely qualified” to help the company.

“Government officials are more comfortable knowing that Giuliani is advising Purdue,” Udell pointed out. Giuliani, he maintained, “would not take an assignment with a company that he felt was acting in an improper way.”

Shortly after Rudolph Giuliani stepped down from his position as mayor of New York City, he went into business as a consultant, and one of his first clients was Purdue. When he entered the private sector, Giuliani was looking to make a lot of money quickly. In 2001, he had a net worth of $1 million; five years later, he would report $17 million in income and some $50 million in assets. For Purdue, which was working hard to frame OxyContin abuse as a law enforcement problem, rather than an issue that might implicate the drug itself or the way it was marketed, the former prosecutor who had led New York City after the 9/ 11 attacks would make an ideal fixer. In Michael Friedman’s view, Giuliani was “uniquely qualified” to help the company.

“Government officials are more comfortable knowing that Giuliani is advising Purdue,” Udell pointed out. Giuliani, he maintained, “would not take an assignment with a company that he felt was acting in an improper way.”

Saturday, January 21, 2023

the last book I ever read (Empire of Pain: The Secret History of the Sackler Family, excerpt nine)

from Empire of Pain: The Secret History of the Sackler Family by Patrick Radden Keefe:

In some ways, Richard’s argument about OxyContin mirrored the libertarian position of a firearms manufacturer who insists that he bears no responsibility for gun deaths. Guns don’t kill people; people kill people. It is a peculiar hallmark of the American economy that you can produce a dangerous product and effectively off-load any legal liability for whatever destruction that product may cause by pointing to the individual responsibility of the consumer. “Abusers aren’t victims,” Richard said. “They are the victimizers.”

There were a number of problems with this hypothesis, but the most significant flaw was that not everyone who developed a problem with OxyContin started out as a recreational abuser. In fact, many people who were prescribed the drug for legitimate pain conditions and took it precisely as the doctor ordered found that they, too, had become hopelessly addicted. In 2002, a twenty-nine-year-old New Jersey woman named Jill Skolek was prescribed OxyContin for a back injury. One night, after four months on the drug, she died in her sleep from respiratory arrest, leaving behind a six-year-old son. Her mother, Marianne Skolek, was a nurse. Distraught and bewildered, she became convinced that OxyContin was dangerous. Skolek wrote to FDA officials, demanding that they do something about Purdue’s aggressive marketing of the drug. At one point, she attended a conference on addiction at Columbia University, where Robin Hogen, a Purdue public relations man, was one of the presenters. Hogen had sandy hair and an Ivy League affect; he wore a pin-striped suit and a bow tie. With a breezy confidence, he informed Skolek that she seemed to have misunderstood the circumstances of her own daughter’s death. The drug wasn’t the problem, Hogen said. The problem was Jill, her daughter. “We think she abused drugs,” he said. (Hogen subsequently apologized.)

In some ways, Richard’s argument about OxyContin mirrored the libertarian position of a firearms manufacturer who insists that he bears no responsibility for gun deaths. Guns don’t kill people; people kill people. It is a peculiar hallmark of the American economy that you can produce a dangerous product and effectively off-load any legal liability for whatever destruction that product may cause by pointing to the individual responsibility of the consumer. “Abusers aren’t victims,” Richard said. “They are the victimizers.”

There were a number of problems with this hypothesis, but the most significant flaw was that not everyone who developed a problem with OxyContin started out as a recreational abuser. In fact, many people who were prescribed the drug for legitimate pain conditions and took it precisely as the doctor ordered found that they, too, had become hopelessly addicted. In 2002, a twenty-nine-year-old New Jersey woman named Jill Skolek was prescribed OxyContin for a back injury. One night, after four months on the drug, she died in her sleep from respiratory arrest, leaving behind a six-year-old son. Her mother, Marianne Skolek, was a nurse. Distraught and bewildered, she became convinced that OxyContin was dangerous. Skolek wrote to FDA officials, demanding that they do something about Purdue’s aggressive marketing of the drug. At one point, she attended a conference on addiction at Columbia University, where Robin Hogen, a Purdue public relations man, was one of the presenters. Hogen had sandy hair and an Ivy League affect; he wore a pin-striped suit and a bow tie. With a breezy confidence, he informed Skolek that she seemed to have misunderstood the circumstances of her own daughter’s death. The drug wasn’t the problem, Hogen said. The problem was Jill, her daughter. “We think she abused drugs,” he said. (Hogen subsequently apologized.)

Friday, January 20, 2023

the last book I ever read (Empire of Pain: The Secret History of the Sackler Family, excerpt eight)

from Empire of Pain: The Secret History of the Sackler Family by Patrick Radden Keefe:

In February 2000, the top federal prosecutor in Maine, Jay McCloskey, sent a letter to thousands of doctors across the state, warning them about the increasing dangers of abuse and “diversion” of OxyContin. Howard Udell, when he learned of McCloskey’s letter, was dismissive. He derided McCloskey as “some overly zealous prosecutor with political ambition” who was just “trying to grab a headline.” But this was a federal official, raising the alarm about a drug that was now generating $ 1 billion a year. So, several months later, Udell flew to Maine, along with Michael Friedman, to meet with McCloskey personally. The prosecutor was concerned about increasingly rampant abuse of OxyContin. Kids were taking the drug, he said. Bright kids. It was ruining their lives. He found it a little strange that his small state had now become one of the highest consumers of OxyContin, per capita, in the nation. McCloskey mentioned the jumbo 160-milligram pills. “One of the doctors up here told me that one of these tablets could kill a kid if swallowed,” he said. “Is that so?”

“Probably,” Udell and Friedman acknowledged.

In February 2000, the top federal prosecutor in Maine, Jay McCloskey, sent a letter to thousands of doctors across the state, warning them about the increasing dangers of abuse and “diversion” of OxyContin. Howard Udell, when he learned of McCloskey’s letter, was dismissive. He derided McCloskey as “some overly zealous prosecutor with political ambition” who was just “trying to grab a headline.” But this was a federal official, raising the alarm about a drug that was now generating $ 1 billion a year. So, several months later, Udell flew to Maine, along with Michael Friedman, to meet with McCloskey personally. The prosecutor was concerned about increasingly rampant abuse of OxyContin. Kids were taking the drug, he said. Bright kids. It was ruining their lives. He found it a little strange that his small state had now become one of the highest consumers of OxyContin, per capita, in the nation. McCloskey mentioned the jumbo 160-milligram pills. “One of the doctors up here told me that one of these tablets could kill a kid if swallowed,” he said. “Is that so?”

“Probably,” Udell and Friedman acknowledged.

Thursday, January 19, 2023

the last book I ever read (Empire of Pain: The Secret History of the Sackler Family, excerpt seven)

from Empire of Pain: The Secret History of the Sackler Family by Patrick Radden Keefe:

Different drugs have different “personalities,” Michael Friedman liked to say. When he and Richard were trying to decide how to position OxyContin in the marketplace, they made a surprising discovery. The personality of morphine was, clearly, that of a powerful drug of last resort. The very name could conjure up the whiff of death. But, as Friedman pointed out to Richard in an email, oxycodone had a very different personality. In their market research, the team at Purdue had realized that many physicians regarded oxycodone as “weaker than morphine,” Friedman said. Oxycodone was less well known, and less well understood, and it had a personality that seemed less threatening and more approachable.

From a marketing point of view, this represented a major opportunity. Purdue could market OxyContin as a safer, less extreme alternative to morphine. A century earlier, Bayer had marketed heroin as morphine without the unpleasant side effects, even though heroin was actually more powerful than morphine and every bit as addictive. Now, in internal discussions at Purdue headquarters in Norwalk, Richard and his colleagues entertained the notion of a similar marketing strategy. In truth, oxycodone wasn’t weaker than morphine, either. In fact it was roughly twice as potent. The marketing specialists at Purdue didn’t know why, exactly, doctors had this misapprehension about its being weaker, but it might have been because for most physicians their chief exposure to oxycodone involved the drugs Percocet and Percodan, in which a small dose of oxycodone was combined with acetaminophen or aspirin. Whatever the reason, Richard and his senior executives now devised a cunning strategy, which they outlined in a series of emails. If the true personality of oxycodone was misunderstood by America’s doctors, the company would not correct that misunderstanding. Instead, they would exploit it.

Different drugs have different “personalities,” Michael Friedman liked to say. When he and Richard were trying to decide how to position OxyContin in the marketplace, they made a surprising discovery. The personality of morphine was, clearly, that of a powerful drug of last resort. The very name could conjure up the whiff of death. But, as Friedman pointed out to Richard in an email, oxycodone had a very different personality. In their market research, the team at Purdue had realized that many physicians regarded oxycodone as “weaker than morphine,” Friedman said. Oxycodone was less well known, and less well understood, and it had a personality that seemed less threatening and more approachable.

From a marketing point of view, this represented a major opportunity. Purdue could market OxyContin as a safer, less extreme alternative to morphine. A century earlier, Bayer had marketed heroin as morphine without the unpleasant side effects, even though heroin was actually more powerful than morphine and every bit as addictive. Now, in internal discussions at Purdue headquarters in Norwalk, Richard and his colleagues entertained the notion of a similar marketing strategy. In truth, oxycodone wasn’t weaker than morphine, either. In fact it was roughly twice as potent. The marketing specialists at Purdue didn’t know why, exactly, doctors had this misapprehension about its being weaker, but it might have been because for most physicians their chief exposure to oxycodone involved the drugs Percocet and Percodan, in which a small dose of oxycodone was combined with acetaminophen or aspirin. Whatever the reason, Richard and his senior executives now devised a cunning strategy, which they outlined in a series of emails. If the true personality of oxycodone was misunderstood by America’s doctors, the company would not correct that misunderstanding. Instead, they would exploit it.

Wednesday, January 18, 2023

the last book I ever read (Empire of Pain: The Secret History of the Sackler Family, excerpt six)

from Empire of Pain: The Secret History of the Sackler Family by Patrick Radden Keefe:

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, which occupied a grand location on Fifth Avenue, jutting into Central Park, had originally been conceived in the immediate aftermath of the Civil War, when a group of prominent New Yorkers decided that the United States needed a great art museum to rival those of Europe. The museum was incorporated in 1870 and moved into the Fifth Avenue site a decade later. It started with a private art collection, consisting mostly of European paintings, which was a gift from John Taylor Johnston, a railroad tycoon, along with donations from some of his fellow robber barons. But from the very beginning, the museum exhibited a fascinating tension between the interests and indulgences of its coterie of wealthy backers and a more public-minded, egalitarian mission. The Met would be free, and open to the public, but subsidized by gifts from the rich. At the dedication of the museum, in 1880, one of its trustees, the lawyer Joseph Choate, gave a speech to the Gilded Age industrialists who had assembled and, in a bid for their support, offered the sly observation that what philanthropy really buys is immortality: “Think of it, ye millionaires of many markets, what glory may yet be yours, if you only listen to our advice, to convert pork into porcelain, grain and produce into priceless pottery, the rude ores of commerce into sculptured marble.” Railroad shares and mining stocks—which in the next financial panic “shall surely perish, like parched scrolls”—could be turned into a durable legacy, Choate suggested, into “glorified canvases of the world’s masters, which shall adorn these walls for centuries.” Through such transubstantiation, he proposed, great fortunes could pass into enduring civic institutions. Over time, the crude origins of any given clan’s largesse might be forgotten, and instead future generations would remember only the philanthropic legacy, prompted to do so by the family’s name on some gallery, some wing, perhaps even on the building itself.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, which occupied a grand location on Fifth Avenue, jutting into Central Park, had originally been conceived in the immediate aftermath of the Civil War, when a group of prominent New Yorkers decided that the United States needed a great art museum to rival those of Europe. The museum was incorporated in 1870 and moved into the Fifth Avenue site a decade later. It started with a private art collection, consisting mostly of European paintings, which was a gift from John Taylor Johnston, a railroad tycoon, along with donations from some of his fellow robber barons. But from the very beginning, the museum exhibited a fascinating tension between the interests and indulgences of its coterie of wealthy backers and a more public-minded, egalitarian mission. The Met would be free, and open to the public, but subsidized by gifts from the rich. At the dedication of the museum, in 1880, one of its trustees, the lawyer Joseph Choate, gave a speech to the Gilded Age industrialists who had assembled and, in a bid for their support, offered the sly observation that what philanthropy really buys is immortality: “Think of it, ye millionaires of many markets, what glory may yet be yours, if you only listen to our advice, to convert pork into porcelain, grain and produce into priceless pottery, the rude ores of commerce into sculptured marble.” Railroad shares and mining stocks—which in the next financial panic “shall surely perish, like parched scrolls”—could be turned into a durable legacy, Choate suggested, into “glorified canvases of the world’s masters, which shall adorn these walls for centuries.” Through such transubstantiation, he proposed, great fortunes could pass into enduring civic institutions. Over time, the crude origins of any given clan’s largesse might be forgotten, and instead future generations would remember only the philanthropic legacy, prompted to do so by the family’s name on some gallery, some wing, perhaps even on the building itself.

Tuesday, January 17, 2023

the last book I ever read (Empire of Pain: The Secret History of the Sackler Family, excerpt five)

from Empire of Pain: The Secret History of the Sackler Family by Patrick Radden Keefe:

In 1965, the federal government started to investigate Librium and Valium. An advisory committee of the Food and Drug Administration recommended that the tranquilizers be treated as controlled substances—a move that would make it much harder for consumers to get them. Both Roche and Arthur Sackler perceived this prospect as a major threat. As a general rule, Arthur was skeptical of government regulation when it came to medicine, and he recognized that new controls on the minor tranquilizers could be devastating for his bottom line. For nearly a decade, the company resisted efforts by the FDA to control Librium and Valium, a period in which Roche sold hundreds of millions of dollars of the drugs. It was only in 1973 that Roche agreed to “voluntarily” submit to the controls. But one FDA adviser would speculate that the timing of this reversal was no accident: at the point when Roche conceded defeat, its patents on the drugs were set to expire, meaning that Roche would no longer enjoy the exclusive right to manufacture them and would be forced to lower its prices in the face of generic competition. As Arthur’s friend and secret business partner Bill Frohlich had observed, the commercial life span of a branded drug is the short interval between the point when you start marketing it and the point when you lose patent exclusivity. Roche and Arthur didn’t need to fight off regulation forever; they just needed to hold it off until the patents had run out.

By the time Roche allowed its tranquilizers to be controlled, Valium had become part of the lives of some twenty million Americans, the most widely consumed—and most widely abused—prescription drug in the world. It had taken time for the country to wake up to the negative impact of Valium, in part because there was some novelty, for average consumers, in the idea of a drug that could be dangerous even though it was prescribed by a doctor. Moral panics over drugs in America had tended to focus on street drugs and to play on fears about minority groups, immigrants, and illicit influences; the idea that you could get hooked on a pill that was prescribed to you by a physician in a white coat with a stethoscope around his neck and a diploma on the wall was somewhat new. But, eventually, establishment figures like the former first lady Betty Ford would acknowledge having struggled with Valium, and Senator Edward Kennedy would blame tranquilizers for producing “a nightmare of dependence and addiction.” Roche stood accused of “overpromoting” the drug. The Rolling Stones even wrote a song about Valium, “Mother’s Little Helper,” whose lyrics evoked the McAdams campaign aimed at women. “Mother needs something today to calm her down,” Mick Jagger sang. “And though she’s not really ill, there’s a little yellow pill.”

In 1965, the federal government started to investigate Librium and Valium. An advisory committee of the Food and Drug Administration recommended that the tranquilizers be treated as controlled substances—a move that would make it much harder for consumers to get them. Both Roche and Arthur Sackler perceived this prospect as a major threat. As a general rule, Arthur was skeptical of government regulation when it came to medicine, and he recognized that new controls on the minor tranquilizers could be devastating for his bottom line. For nearly a decade, the company resisted efforts by the FDA to control Librium and Valium, a period in which Roche sold hundreds of millions of dollars of the drugs. It was only in 1973 that Roche agreed to “voluntarily” submit to the controls. But one FDA adviser would speculate that the timing of this reversal was no accident: at the point when Roche conceded defeat, its patents on the drugs were set to expire, meaning that Roche would no longer enjoy the exclusive right to manufacture them and would be forced to lower its prices in the face of generic competition. As Arthur’s friend and secret business partner Bill Frohlich had observed, the commercial life span of a branded drug is the short interval between the point when you start marketing it and the point when you lose patent exclusivity. Roche and Arthur didn’t need to fight off regulation forever; they just needed to hold it off until the patents had run out.

By the time Roche allowed its tranquilizers to be controlled, Valium had become part of the lives of some twenty million Americans, the most widely consumed—and most widely abused—prescription drug in the world. It had taken time for the country to wake up to the negative impact of Valium, in part because there was some novelty, for average consumers, in the idea of a drug that could be dangerous even though it was prescribed by a doctor. Moral panics over drugs in America had tended to focus on street drugs and to play on fears about minority groups, immigrants, and illicit influences; the idea that you could get hooked on a pill that was prescribed to you by a physician in a white coat with a stethoscope around his neck and a diploma on the wall was somewhat new. But, eventually, establishment figures like the former first lady Betty Ford would acknowledge having struggled with Valium, and Senator Edward Kennedy would blame tranquilizers for producing “a nightmare of dependence and addiction.” Roche stood accused of “overpromoting” the drug. The Rolling Stones even wrote a song about Valium, “Mother’s Little Helper,” whose lyrics evoked the McAdams campaign aimed at women. “Mother needs something today to calm her down,” Mick Jagger sang. “And though she’s not really ill, there’s a little yellow pill.”

Sunday, January 15, 2023

the last book I ever read (Empire of Pain: The Secret History of the Sackler Family, excerpt four)

from Empire of Pain: The Secret History of the Sackler Family by Patrick Radden Keefe:

Just as women had outnumbered men in the wards of Creedmoor, it now emerged that doctors were prescribing Roche’s tranquilizers to women much more often than to men, and Arthur and his colleagues seized on this phenomenon and started to aggressively market Librium and Valium to women. In describing an ideal patient, a typical ad for Valium read, “35, single and psychoneurotic.” An early ad for Librium showed a young woman with an armful of books and suggested that even the routine stress of heading off to college might be best addressed with Librium. But the truth was, Librium and Valium were marketed using such a variety of gendered mid-century tropes—the neurotic singleton, the frazzled housewife, the joyless career woman, the menopausal shrew—that as the historian Andrea Tone noted in her book The Age of Anxiety, what Roche’s tranquilizers really seemed to offer was a quick fix for the problem of “being female.”

Roche was hardly the only company to employ this sort of over-the-top disingenuous advertising. Pfizer had a tranquilizer that it recommended for use by children with an illustration of a young girl with a tearstained face and a suggestion that the drug could alleviate fears of “school, the dark, separation, dental visits, ‘monsters.’ ” But once Roche and Arthur Sackler unleashed Librium and Valium, no other company could compete. At Roche’s plant in Nutley, mammoth pill-stamping machines struggled to keep up with demand, churning out tens of millions of tablets a day. Initially, Librium was the most prescribed drug in America, until it was overtaken by Valium in 1968. But even then, Librium held on, remaining in the top five. In 1964, some twenty-two million prescriptions were written for Valium. By 1975, that figure reached sixty million. Valium was the first $ 100 million drug in history, and Roche became not just the leading drug company in the world but one of the most profitable companies of any kind. Money was pouring in, and when it did, the company turned around and reinvested that money in the promotion campaign devised by Arthur Sackler.

Just as women had outnumbered men in the wards of Creedmoor, it now emerged that doctors were prescribing Roche’s tranquilizers to women much more often than to men, and Arthur and his colleagues seized on this phenomenon and started to aggressively market Librium and Valium to women. In describing an ideal patient, a typical ad for Valium read, “35, single and psychoneurotic.” An early ad for Librium showed a young woman with an armful of books and suggested that even the routine stress of heading off to college might be best addressed with Librium. But the truth was, Librium and Valium were marketed using such a variety of gendered mid-century tropes—the neurotic singleton, the frazzled housewife, the joyless career woman, the menopausal shrew—that as the historian Andrea Tone noted in her book The Age of Anxiety, what Roche’s tranquilizers really seemed to offer was a quick fix for the problem of “being female.”

Roche was hardly the only company to employ this sort of over-the-top disingenuous advertising. Pfizer had a tranquilizer that it recommended for use by children with an illustration of a young girl with a tearstained face and a suggestion that the drug could alleviate fears of “school, the dark, separation, dental visits, ‘monsters.’ ” But once Roche and Arthur Sackler unleashed Librium and Valium, no other company could compete. At Roche’s plant in Nutley, mammoth pill-stamping machines struggled to keep up with demand, churning out tens of millions of tablets a day. Initially, Librium was the most prescribed drug in America, until it was overtaken by Valium in 1968. But even then, Librium held on, remaining in the top five. In 1964, some twenty-two million prescriptions were written for Valium. By 1975, that figure reached sixty million. Valium was the first $ 100 million drug in history, and Roche became not just the leading drug company in the world but one of the most profitable companies of any kind. Money was pouring in, and when it did, the company turned around and reinvested that money in the promotion campaign devised by Arthur Sackler.

Saturday, January 14, 2023

the last book I ever read (Empire of Pain: The Secret History of the Sackler Family, excerpt three)

from Empire of Pain: The Secret History of the Sackler Family by Patrick Radden Keefe:

In 1949, an unusual advertisement started to appear in a number of medical journals. “Terra bona,” it said, in bold brown letters against a green backdrop. It wasn’t clear what “Terra bona” meant, exactly—or, for that matter, if there was any specific product the advertisement was supposed to be selling. “The great earth has given man more than bread alone,” a caption read, noting that new antibiotics discovered in the soil had succeeded in extending human life. “In the isolation, screening and production of such vital agents, a notable role has been played by…Pfizer.”

For nearly a century, the Brooklyn firm Chas. Pfizer & Company had been a modest supplier of chemicals. Until World War II, outfits like Pfizer sold chemicals in bulk, without brand names, whether to other companies or to pharmacists (who would mix the chemicals themselves). Then, in the early 1940s, the introduction of penicillin ushered in a new era of antibiotics—powerful medications that can stop infections caused by bacteria. When the war broke out, the U.S. military needed great quantities of penicillin to administer to the troops, and companies like Pfizer were enlisted to produce the drug. By the time the war ended, the business model of these chemical companies had forever changed: now they were mass-producing not just chemicals but finished drugs, which were ready for sale. Penicillin was a revolutionary medicine, but it wasn’t patented, which meant that anyone could produce it. Because no company held a monopoly, it remained cheap and, thus, not particularly lucrative. So Pfizer, emboldened, began to hunt for other remedies that it could patent and sell at a higher price.

In 1949, an unusual advertisement started to appear in a number of medical journals. “Terra bona,” it said, in bold brown letters against a green backdrop. It wasn’t clear what “Terra bona” meant, exactly—or, for that matter, if there was any specific product the advertisement was supposed to be selling. “The great earth has given man more than bread alone,” a caption read, noting that new antibiotics discovered in the soil had succeeded in extending human life. “In the isolation, screening and production of such vital agents, a notable role has been played by…Pfizer.”

For nearly a century, the Brooklyn firm Chas. Pfizer & Company had been a modest supplier of chemicals. Until World War II, outfits like Pfizer sold chemicals in bulk, without brand names, whether to other companies or to pharmacists (who would mix the chemicals themselves). Then, in the early 1940s, the introduction of penicillin ushered in a new era of antibiotics—powerful medications that can stop infections caused by bacteria. When the war broke out, the U.S. military needed great quantities of penicillin to administer to the troops, and companies like Pfizer were enlisted to produce the drug. By the time the war ended, the business model of these chemical companies had forever changed: now they were mass-producing not just chemicals but finished drugs, which were ready for sale. Penicillin was a revolutionary medicine, but it wasn’t patented, which meant that anyone could produce it. Because no company held a monopoly, it remained cheap and, thus, not particularly lucrative. So Pfizer, emboldened, began to hunt for other remedies that it could patent and sell at a higher price.

Friday, January 13, 2023

the last book I ever read (Empire of Pain: The Secret History of the Sackler Family, excerpt two)

from Empire of Pain: The Secret History of the Sackler Family by Patrick Radden Keefe:

The favored treatment at Creedmoor during this period was a procedure that was not as invasive but that Arthur nevertheless disdained: electroshock therapy. The treatment had been invented some years earlier by an Italian psychiatrist who arrived at the idea after a visit to a slaughterhouse. Observing how pigs were stunned with a jolt of electricity just before they were killed, he devised a procedure in which electrodes were placed on the temples of a human patient so that a current of electricity could be administered to the temporal lobe and other regions of the brain where memory is processed. The shock caused the patient to convulse, then lapse into unconsciousness. When she came to, she was often disoriented and nauseous. Some patients experienced memory loss. Others felt profoundly shaken after the procedure and did not know who they were. But for all of its blunt force, electroshock therapy did seem to offer relief to many patients. It appeared to alleviate intense depression and to soothe people who were experiencing psychotic episodes; it might not have been a cure for schizophrenia, but it could often mitigate the symptoms.

Nobody understood why exactly this treatment might work. They just knew that it did. And at a place like Creedmoor, that was enough. The therapy was first used in the hospital in 1942 and was eventually administered to thousands of patients. To be sure, there were side effects. The convulsions that patients experienced as the electric charge pulsed through their heads were painful and deeply frightening. The poet Sylvia Plath, who was administered electroshock treatment at a hospital in Massachusetts during this period, described how it felt as if “a great jolt drubbed me till I thought my bones would break and the sap fly out of me like a split plant.” The singer Lou Reed, who received electroshock treatment at Creedmoor in 1959, was temporarily debilitated by the ordeal, which left him, in the words of his sister, “stupor-like” and unable to walk.

The favored treatment at Creedmoor during this period was a procedure that was not as invasive but that Arthur nevertheless disdained: electroshock therapy. The treatment had been invented some years earlier by an Italian psychiatrist who arrived at the idea after a visit to a slaughterhouse. Observing how pigs were stunned with a jolt of electricity just before they were killed, he devised a procedure in which electrodes were placed on the temples of a human patient so that a current of electricity could be administered to the temporal lobe and other regions of the brain where memory is processed. The shock caused the patient to convulse, then lapse into unconsciousness. When she came to, she was often disoriented and nauseous. Some patients experienced memory loss. Others felt profoundly shaken after the procedure and did not know who they were. But for all of its blunt force, electroshock therapy did seem to offer relief to many patients. It appeared to alleviate intense depression and to soothe people who were experiencing psychotic episodes; it might not have been a cure for schizophrenia, but it could often mitigate the symptoms.

Nobody understood why exactly this treatment might work. They just knew that it did. And at a place like Creedmoor, that was enough. The therapy was first used in the hospital in 1942 and was eventually administered to thousands of patients. To be sure, there were side effects. The convulsions that patients experienced as the electric charge pulsed through their heads were painful and deeply frightening. The poet Sylvia Plath, who was administered electroshock treatment at a hospital in Massachusetts during this period, described how it felt as if “a great jolt drubbed me till I thought my bones would break and the sap fly out of me like a split plant.” The singer Lou Reed, who received electroshock treatment at Creedmoor in 1959, was temporarily debilitated by the ordeal, which left him, in the words of his sister, “stupor-like” and unable to walk.

Thursday, January 12, 2023

the last book I ever read (Empire of Pain: The Secret History of the Sackler Family, excerpt one)

from Empire of Pain: The Secret History of the Sackler Family by Patrick Radden Keefe:

Arthur had a relentlessly analytical mind, and as he evaluated this dilemma, he concluded that the practical problem was that mental disorders appeared to be growing at a faster rate than the ability of the authorities to build asylums. A stroll through the overcrowded wards of Creedmoor would tell you that. What Arthur wanted to do was come up with a solution. Something that worked. The challenge, when it came to mental illness, was efficacy: perform a surgery, and you’ll generally be able to judge, before too long, whether the procedure was a success. But tinkering with the brain was more difficult to measure. And the fact that it was hard to evaluate results in this manner had led to some truly outlandish experiments. Just a few decades earlier, the superintendent of a state hospital in New Jersey had become convinced that the way to cure insanity was to remove a patient’s teeth. When some of his patients did not appear to respond to this course of treatment, the superintendent kept going, removing tonsils, colons, gallbladders, appendixes, fallopian tubes, uteruses, ovaries, cervixes. In the end, he cured no patients with these experiments, but he did kill more than a hundred of them.

Arthur had a relentlessly analytical mind, and as he evaluated this dilemma, he concluded that the practical problem was that mental disorders appeared to be growing at a faster rate than the ability of the authorities to build asylums. A stroll through the overcrowded wards of Creedmoor would tell you that. What Arthur wanted to do was come up with a solution. Something that worked. The challenge, when it came to mental illness, was efficacy: perform a surgery, and you’ll generally be able to judge, before too long, whether the procedure was a success. But tinkering with the brain was more difficult to measure. And the fact that it was hard to evaluate results in this manner had led to some truly outlandish experiments. Just a few decades earlier, the superintendent of a state hospital in New Jersey had become convinced that the way to cure insanity was to remove a patient’s teeth. When some of his patients did not appear to respond to this course of treatment, the superintendent kept going, removing tonsils, colons, gallbladders, appendixes, fallopian tubes, uteruses, ovaries, cervixes. In the end, he cured no patients with these experiments, but he did kill more than a hundred of them.

Wednesday, January 11, 2023

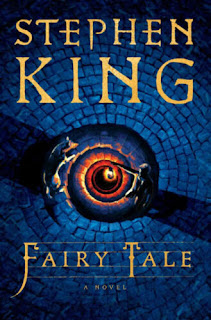

the last book I ever read (Stephen King's Fairy Tale: A Novel, excerpt ten)

from Fairy Tale: A Novel by Stephen King:

In the center of the lobby were a number of red-painted kiosks, not much different from the ones my dad and I had passed through many times at Guaranteed Rate Field when we went to Chicago to see the White Sox play. “I know where we are,” Iota muttered.

He pointed. “Wait, Charlie. One minute.” He pounded up one of the ramps, looked, and ran back.

“The seats are empty. So is the field. They’ve all gone. Bodies, as well.”

In the center of the lobby were a number of red-painted kiosks, not much different from the ones my dad and I had passed through many times at Guaranteed Rate Field when we went to Chicago to see the White Sox play. “I know where we are,” Iota muttered.

He pointed. “Wait, Charlie. One minute.” He pounded up one of the ramps, looked, and ran back.

“The seats are empty. So is the field. They’ve all gone. Bodies, as well.”

Tuesday, January 10, 2023

the last book I ever read (Stephen King's Fairy Tale: A Novel, excerpt nine)

from Fairy Tale: A Novel by Stephen King:

Leah gave a muffled groan that would have been a scream if it had been able to escape her. She put her hands over her eyes and collapsed on one of the benches where Empisarians who had made the trek from their towns and villages might once have sat to marvel at the beautiful creature swimming in the pool, and perhaps to listen to a song. She bent over her thighs, still making those muffled groaning sounds, which to me were more terrible—more bereft—than actual sobs would have been. I put my hand on her back, suddenly afraid that her inability to fully voice her grief might kill her, the way an unlucky person could choke to death on a lodgment of food in the throat.

Leah gave a muffled groan that would have been a scream if it had been able to escape her. She put her hands over her eyes and collapsed on one of the benches where Empisarians who had made the trek from their towns and villages might once have sat to marvel at the beautiful creature swimming in the pool, and perhaps to listen to a song. She bent over her thighs, still making those muffled groaning sounds, which to me were more terrible—more bereft—than actual sobs would have been. I put my hand on her back, suddenly afraid that her inability to fully voice her grief might kill her, the way an unlucky person could choke to death on a lodgment of food in the throat.

Monday, January 9, 2023

the last book I ever read (Stephen King's Fairy Tale: A Novel, excerpt eight)

from Fairy Tale: A Novel by Stephen King:

Iota had no interest in such philosophical postulates. He said, “Tis also told that on the night when the sky-sisters kiss, every evil thing is set free to work wickedness on the world.” He paused. “When I was a youngster we were forbidden to go out on nights when the sisters kissed. The wolves howled, the wind howled, but not just the wolves and the wind.” He looked at me somberly. “Charlie, the world howled. As if it was in pain.”

Iota had no interest in such philosophical postulates. He said, “Tis also told that on the night when the sky-sisters kiss, every evil thing is set free to work wickedness on the world.” He paused. “When I was a youngster we were forbidden to go out on nights when the sisters kissed. The wolves howled, the wind howled, but not just the wolves and the wind.” He looked at me somberly. “Charlie, the world howled. As if it was in pain.”

Sunday, January 8, 2023

the last book I ever read (Stephen King's Fairy Tale: A Novel, excerpt seven)

from Fairy Tale: A Novel by Stephen King:

“How do we get out?” Stooks asked.

Eris said, “Did you never learn to read?”

“As well as any plowboy, I guess,” Stooks said, sounding grumpy. Of course I’d be grumpy, too, if I had to hold my cheek with my hand to keep the food from squirting out.

“How do we get out?” Stooks asked.

Eris said, “Did you never learn to read?”

“As well as any plowboy, I guess,” Stooks said, sounding grumpy. Of course I’d be grumpy, too, if I had to hold my cheek with my hand to keep the food from squirting out.

Saturday, January 7, 2023

the last book I ever read (Stephen King's Fairy Tale: A Novel, excerpt six)

from Fairy Tale: A Novel by Stephen King:

Iota picked the piece of bone out of his forehead and stared around, unbelieving. Shards of bone were everywhere. They looked like broken crockery. All that remained of the night soldiers were their uniforms, which were shredded, as if they had sustained close-range blasts from shotguns loaded with birdshot.

Iota picked the piece of bone out of his forehead and stared around, unbelieving. Shards of bone were everywhere. They looked like broken crockery. All that remained of the night soldiers were their uniforms, which were shredded, as if they had sustained close-range blasts from shotguns loaded with birdshot.

Friday, January 6, 2023

the last book I ever read (Stephen King's Fairy Tale: A Novel, excerpt five)

from Fairy Tale: A Novel by Stephen King:

I was on cold, damp stone. Over Hamey’s scrawny shoulder I could see a wall of blocks oozing water with a barred window high up. Nothing between the bars but black. I was in a cell. Durance vile, I thought. I didn’t know where that phrase came from, wasn’t even sure I knew what it meant. What I knew was that my head ached terribly and the man who’d been slapping me awake had breath so bad it was like some small animal had died in his mouth. Oh, and it seemed I had wet my pants.

Hamey leaned close to me. I tried to draw back, but there were more bars behind me.

I was on cold, damp stone. Over Hamey’s scrawny shoulder I could see a wall of blocks oozing water with a barred window high up. Nothing between the bars but black. I was in a cell. Durance vile, I thought. I didn’t know where that phrase came from, wasn’t even sure I knew what it meant. What I knew was that my head ached terribly and the man who’d been slapping me awake had breath so bad it was like some small animal had died in his mouth. Oh, and it seemed I had wet my pants.

Hamey leaned close to me. I tried to draw back, but there were more bars behind me.

Thursday, January 5, 2023

the last book I ever read (Stephen King's Fairy Tale: A Novel, excerpt four)

from Fairy Tale: A Novel by Stephen King:

An herbage rank and wild, I thought, and that line brought back memories of Jenny Schuster. Sitting with her under a tree, the two of us leaning against the trunk in the dappled shade, her wearing the tattered old vest that was her trademark and holding a paperback book in her lap. It was called The Best of H. P. Lovecraft, and she was reading me a poem called “Fungi from Yuggoth.” I remembered how it began: The place was dark and dusty and half-lost in tangles of old alleys near the quays, and suddenly the reason why this place was freaking me out came into focus. I was still miles from Lilimar—what that refugee boy had called the haunted city—but even here thing were wrong in ways I don’t think I could have consciously understood if not for Jenny, who introduced me to Lovecraft when both of us were sixth graders, too young and impressionable for such horrors.

An herbage rank and wild, I thought, and that line brought back memories of Jenny Schuster. Sitting with her under a tree, the two of us leaning against the trunk in the dappled shade, her wearing the tattered old vest that was her trademark and holding a paperback book in her lap. It was called The Best of H. P. Lovecraft, and she was reading me a poem called “Fungi from Yuggoth.” I remembered how it began: The place was dark and dusty and half-lost in tangles of old alleys near the quays, and suddenly the reason why this place was freaking me out came into focus. I was still miles from Lilimar—what that refugee boy had called the haunted city—but even here thing were wrong in ways I don’t think I could have consciously understood if not for Jenny, who introduced me to Lovecraft when both of us were sixth graders, too young and impressionable for such horrors.

Wednesday, January 4, 2023

the last book I ever read (Stephen King's Fairy Tale: A Novel, excerpt three)

from Fairy Tale: A Novel by Stephen King:

I put the book on the shelf, left the room, then went back again to look at the cover. The inside was full of trudging prose, compound-complex sentences that allowed the eye no rest, but the cover was a little lyric, as perfect in its way as that William Carlos Williams poem about the red wheelbarrow: a funnel filling with stars.

I put the book on the shelf, left the room, then went back again to look at the cover. The inside was full of trudging prose, compound-complex sentences that allowed the eye no rest, but the cover was a little lyric, as perfect in its way as that William Carlos Williams poem about the red wheelbarrow: a funnel filling with stars.

Tuesday, January 3, 2023

the last book I ever read (Stephen King's Fairy Tale: A Novel, excerpt two)

from Fairy Tale: A Novel by Stephen King:

By evening the rasp was gone. I made popcorn, shaking it up old-school on the Hotpoint stove. We ate it while watching Hud on my laptop. It was Mr Bowditch’s pick, I’d never heard of it, but it was pretty good. I didn’t even mind that it wasn’t in color. At one point Mr. Bowditch asked me to freeze the picture while the camera was close-up on Paul Newman. “Was he the handsomest man that ever lived, Charlie? What do you think?”

I said he could be right.

By evening the rasp was gone. I made popcorn, shaking it up old-school on the Hotpoint stove. We ate it while watching Hud on my laptop. It was Mr Bowditch’s pick, I’d never heard of it, but it was pretty good. I didn’t even mind that it wasn’t in color. At one point Mr. Bowditch asked me to freeze the picture while the camera was close-up on Paul Newman. “Was he the handsomest man that ever lived, Charlie? What do you think?”

I said he could be right.

Monday, January 2, 2023

the last book I ever read (Stephen King's Fairy Tale: A Novel, excerpt one)

from Fairy Tale: A Novel by Stephen King:

“Gee, I don’t know. I’d have to have Mr. Bowditch’s permission, and he’s in the hospital.”

“Ask him tomorrow or the next day, would you do that? I’ll have to file the story soon if it’s going to run in next week’s issue.”

“I will if I can, but I think he was scheduled for another operation. They might not let me visit him, and I really can’t do it without his permission.” The last thing I wanted was for Mr. Bowditch to be mad at me, and he was the kind of guy who got mad easily. I looked up the word for people like that later on; it was misanthrope.

“Gee, I don’t know. I’d have to have Mr. Bowditch’s permission, and he’s in the hospital.”

“Ask him tomorrow or the next day, would you do that? I’ll have to file the story soon if it’s going to run in next week’s issue.”

“I will if I can, but I think he was scheduled for another operation. They might not let me visit him, and I really can’t do it without his permission.” The last thing I wanted was for Mr. Bowditch to be mad at me, and he was the kind of guy who got mad easily. I looked up the word for people like that later on; it was misanthrope.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)