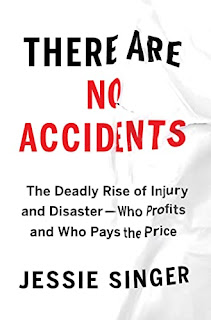

from There Are No Accidents: The Deadly Rise of Injury and Disaster―Who Profits and Who Pays the Price by Jessie Singer:

Maintaining this lie was Richard Sackler’s point about needing to “hammer on abusers.” And for a long time, that stigmatizing strategy worked. Purdue blamed human error for the opiod epidemic, distracting from the dangerous condition of an addictive drug marketed as nonaddictive. All the while, addictions and accidental overdoses grew and grew. Between 1995 and 2001, the number of people treated for opiod abuse in the state of Maine grew by 460 percent. In 2000, West Virginia opened its first methadone treatment program, and then, in the next three years, the state would need to open six more. In 2002, OxyContin prescriptions climbed over 6 million. By 2003, accidental fatal prescriptions overdoses had grown by 830 percent in one corner of Virginia. The Drug Enforcement Administration did not begin to crack down on pain clinics and distributors until 2005. By then, for the addicted, it was too late. In 2021, the vast majority of accidental overdose deaths was still due to opiods. Between 1999 and 2020, well over 840,000 people died of an opiod overdose. As the death toll rose too precipitously to be ignored, the drug companies leaned into this idea: There are no accidental overdoses. There are only reckless criminal addicts.

“Once it became clear that addiction was a problem, the drug companies’ first line of defense, and an incredibly successful one, was to say: Look, our products are good, the doctors are good, the patients are good, but there are these evil abusers,” Herzberg tells me. “They are becoming addicted and giving our drug a bad name. So, we should respond to this, not as if this is a crisis of accidents, we should respond to this as if it is a crisis of bad people.”

No comments:

Post a Comment