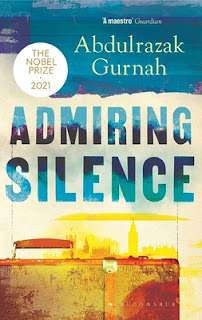

from Admiring Silence by Abdulrazak Gurnah, the 2021 winner of the Nobel Prize for Literature:

When the war came it was possible to do a different kind of business. (He grinned at this point, and although he did not say so, I knew from somewhere I can no longer remember that in the early Forties he had spent a month in prison for smuggling.) Everything was short and rationed, the British needed it for their own people, who were far more important than us. So whatever you could find – rice, sugar, simsim, millet – even if it was of poor quality, there was always a good market for it. Peeple learnt to eat jaggery and brown rice and shellfish when before they would have spurned such food as fit only for servants and heathens.

It was difficult to get news of the war. There were no radios then, or very few, and those who owned radios kept quiet about it because they were afraid they would be confiscated. The British were nervous about everything, so we guessed that things were not going well for them. It was not a surprise. We knew the Germans and how they made war. Some of the riff-raff here joined up, and some young people who were still at school did so too, because they were promised that they would be sent to a big college when they returned, and would all become doctors and lawyers. It’s a good thing you didn’t become a lawyer, their business is to cheat. Or a policeman, because if you are a policeman and they order you to arrest your mother you have no choice but to obey, and God has said Honour your father and your mother after Me. So if you become a policeman, you are also saying that you are prepared to disobey God if the need arises. Anyway, they were sent to Abyssinia to fight the Italians and to Burma to fight the Japanese, and we didn’t see them again until the end of the war, those who came back. The ones who had joined up from school asked about their big college, and they were sent to the teachers’ college in Beit-el-Ras, and others became policemen after all.

No comments:

Post a Comment